(3 August 1938 – 17 July 2021)

(Obituary kindly provided by Tom Stanier, Robin’s brother)

Our father, Bob Stanier, was appointed Master of Magdalen College School in 1944, and the Stanier family moved in to the Boarding House as our new residence. Robin was aged 6 and I was aged 3, and our arrival was saluted rather charmingly by an editorial in the Lily, December 1944

‘And lastly, for the benefit of those who in the precincts of School House have not been prodded in the back with sticks, whipped round the legs with knotted ropes, bowled’ over by little bicycles or leaped out upon from behind corners, we should like to say that Mr. and Mrs. Stanier have two sons, aged six and three respectively, and that it is our pleasure to dedicate this term’s issue of the Lily to—Robin and Tom.’

As we grew up we became increasingly sports mad , and revelled in our surroundings. As Robin said to me recently, ‘We had the River, the Spit and the most beautiful Playing Fields in the country. What more could two boys possibly want?’ It was a formative environment for us, as it must have been for so many Old Waynfletes.

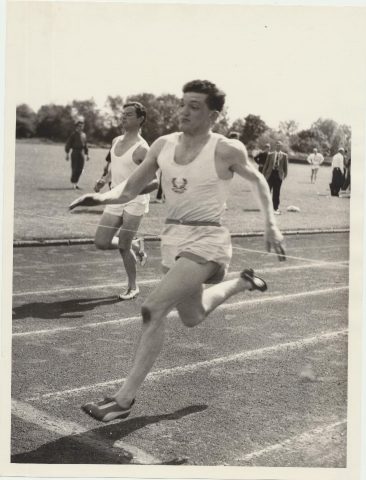

Robin did well at Berkhamsted, and flourished on the sports fields. He broke the 220 yards record , opened the batting for the School in cavalier fashion , and captained a Rugby team that went through the season unbeaten for the first time in living memory, though we nearly came unstuck against MCS. I recently came across a cutting from the Oxford Mail that my mother, Maida , had squirrelled away. Under the headline ‘MASTER’S SON HELPS TO BEAT MCS, it opened : Due mainly to fine place kicking by Robin Stanier, the Berkhamsted captain, Berkhamsted won their 7th game , keeping their unbeaten record. Mr Stanier’s younger son, Tom, also played for Berkhamsted at scrum half.’ I suspect this was written by an Old Waynflete, John Parsons, who was cutting his journalistic teeth at the time on the local paper, before going on to be Tennis Correspondent for the Daily Telegraph.

From school Robin went up to Magdalen in 1957 to read Engineering. Students in those days were required to be back in college by midnight, and Robin’s athletic prowess came in very handy. He found that if he heard midnight start to strike while visiting his parents , he could then sprint the 200 yards back to College before the midnight chimes had completed and so avoid the obligatory fine. In a more conventional athletic environment he also ran in the 4 x 220 yards relays for Oxford against Cambridge.

Robin had always had a particular interest in aeroplanes. After graduating, he worked for two years with Rolls Royce in Derby on aero engine development. He then developed itchy feet. He spotted a job going in Australia and wanderlust plus the twin temptations of doubling his salary and a first class ticket to Australia carried the day. It was to prove a happy decision. Within two years he had married a Queensland girl, Rosey Hopkins, and settled down in Canberra to combine a very happy family life with working for the Australian government on various aeronautical projects. The cost of flights to and from the UK in those early days was astronomical and I was very touched when Robin agreed in 1965 to become Best Man at my wedding. I only discovered much later that the ticket to the UK had cost him a third of his salary.

Robin never lost of his interest in aeroplanes, and was particularly proud of his involvement in the Nomad Searchmaster Project. The Searchmaster planes were designed to detect drug smuggler boats through infra-red detection and radar equipment at night time. So successful were they that the drug traffic in Australia was severely curtailed and redirected by the smugglers to land routes through Mexico. Two months before he died, Robin was profoundly gratified when the Royal Aeronautical Society of Australia gave him a Distinguished Service Award.

Robin’ sons are all passionate supporters of Australian sporting teams. Robin was initially loyal to England, but as the years went by, he ‘went native’ and transferred his loyalties. On the last day of his life – by a wonderful piece of timing – he and his sons watched on television as 14-man Australia held on to score a nail-biting victory over France. Robin was spellbound. An hour later he died. What a way to go.

MCS ranks among the top independent secondary schools, and in 2024 was awarded Independent School of the Year for our contribution to social mobility.

MCS ranks among the top independent secondary schools, and in 2024 was awarded Independent School of the Year for our contribution to social mobility.

28 of our pupils achieved 10 or more 8 or 9 grades in 2024.

28 of our pupils achieved 10 or more 8 or 9 grades in 2024.

In 2023-24, MCS received over £448,000 in donated funds.

In 2023-24, MCS received over £448,000 in donated funds.